Achieving the new plastics economy

Also, download this story from the electronic issue here

Plastics as a valuable resource is at the core of the New Plastics Economy agenda; at its base is every individual’s responsibility to manage plastic waste properly, says Angelica Buan in this report.

Worsening climate change and unprecedented marine litter are two of the millennium’s worst environmental nightmares. The menace is the proliferation of discarded plastics. But is the hype against waste plastics too much ado about nothing?

Granted that plastic is more carbon efficient than other traditional materials in certain applications, the material is still liable for the millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, some experts say. Also, is the fact that it takes about 4% of the world’s non-renewable oil resource to produce plastic and an additional 3 to 4% for energy consumption during manufacture.

Moreover, the convenience that plastic delivers, especially in packaging, is a catch-22 situation. It is easier to throw packaging away, to such a degree that it has come to be a major marine pollutant due to its resilience against degradation.

Initiatives to curb plastics use as well as clean-up of dumping grounds and water systems alike can only do as much to ease the problem. More than an option but a conscious effort to mitigate the impact of used plastics in the environment is, of course, recovering and recycling plastics for end-of-life waste management.

The market for recycled plastics has been soft of late. The plunge in oi l pr ices has not helped the recycling industry , which is at the same time combating issues like the quality of recycled plastic grades and pricing.

Circular economy: remodelling the plastics economy

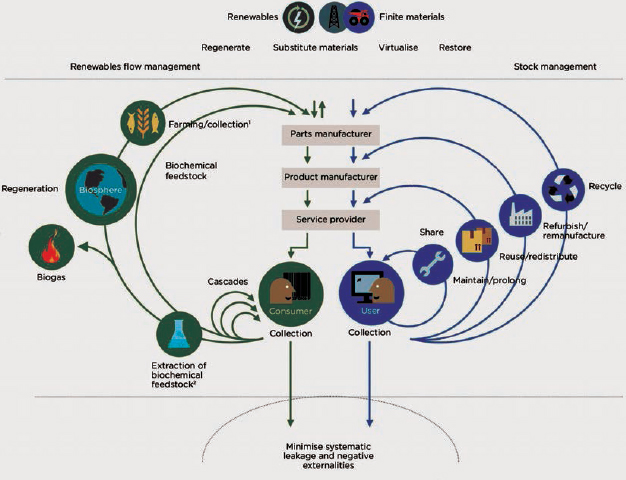

A circular economy posits an effective response to the waste plastics dilemma. It is, in this case, producing plastics minus waste and pollution, either by design or intention. It is restorative and regenerative by design, and aims to keep products, components, and materials at their highest utility and value at all times, says Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) , a UK-registered charity.

EMF calls it a “linear take, make, dispose economic model”, since this is nearing its physical limits; as well, the raw materials and energy that go into the production of plastics are too valuable and are not limitless.

EMF, together with World Economic Forum (WEF) also initiated a report, The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics, drawing the premise that the growing volumes of end-of-use plastics are generating costs and destroying value to the industry. After-use plastics, with circular economy thinking, are turned into valuable feedstock.

This situation mostly resonates with packaging since it is used only once; 95% of the value of plastic packaging material, worth as much as US$120 billion annually, is lost to the economy. In particular, the report says that the fastmoving consumer goods sector – in the context of the linear consumption pattern – sends goods estimated to be worth over US$2.6 trillion annually to landfills and incinerator facilities.

The New Plastics Economy aims to provide insights on new afteruse pathways for plast ics. I t can strategically truncate incidences of plastics entering water systems, as well, decouple plastics from fossil feedstocks.

The call for a circular economy to be implemented across the global plastics value chain has been backed by major companies , inc luding ones that are into consumer goods, packaging , manufacturing and recycling. Additionally, the report indicates that shifting to a circular model could generate a US$706 billion economic opportunity, of which, a significant proportion is attributable to packaging.

The proposition indicates several approaches, including improving after-use infrastructure in so-called high-leakage nations (countries that heavily contribute to ocean litter); increasing the value of after-use plastic packaging to reduces the likelihood that it escapes the collection system, especially in countries with an informal waste sector; and developing plastic materials to become less damaging to the marine environment, even if the materials leak outside of collection systems.

Enabling innovations

There are various technologies referred to as “moon shot innovations” being targeted and collaborated on by leading businesses, academics and innovators to enable the New Plastics Economy. Currently, these “focused, practical initiatives with a high potential for significant impact at scale” are in various stages of development. Examples of the innovations are:

- Removing additives from recovered polymers to increase recyclate purity

- Recycling multi-material packaging by designing reversible adhesives that allow for triggered separation of different material layers

- Super-polymers that combine functionality and cost with superior after-use properties

- Recycling plastics to monomer feedstock for virginquality polymers

- Introducing chemical markers for sorting by using dyes, inks or other additive markers detectable by automated sorting/near infrared technology

- Designing plastics to be benign in marine and fresh water environments

- Sourcing biobased plastics from carbon from greenhouse gases

Bioplastics: an under-utilised renewable option

According to Allied Market Research’s World Bioplastics Market - Opportunities and Forecast, 2014 – 2020 report, the bioplastics market is expected to achieve a CAGR of 17.5% from nearly 4,870 kilotonnes in 2014. Despite the optimistic forecast for bioplastics, market growth is not optimised.

Bioplastics are yet to be used to a scale as broad as petroleum-based plastics due to the relatively high cost of producing them. Furthermore, lower oil prices curtail adoption of bioplastics.

Nevertheless, there are countries that are actively promoting the use of bioplastics in the pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and food sectors. For instance, the four-year European project called Dibbiopack that started in 2012, supported by the European Commission (EC) through the Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development, involves a consortium of 19 partners from 11 countries. The EUR7.8 millionproject is developing packaging that is compostable and biodegradable with enhanced functionalities (antimicrobial, with integrated oxygen sensor, enhanced barrier properties, oxygen-absorbing effect on the cap).

Moreover, the project’s objective is to go beyond the regulatory, technological, market and environmental milestones and provide solutions by using nanomaterials, biodegradable films and sensors.

Still in Europe, the revised EU waste legislation penned by MEP Simona Bonafè, Rapporteur of the European Parliament’s Committee on the Environment is supportive of bioplastics and biobased materials in packaging. The draft reports lay out the legal measures needed for a paradigm shift from a linear to a circular economy where waste is considered a valuable resource, and the transformation to a low-carbon bioeconomy, which uses resources more efficiently.

The European Bioplastics (EUBP) commends the report, saying that it encourages better market conditions for renewable raw materials and promotes the use of biobased materials in packaging.

Furthermore, the report on the amendments to the Waste Framework Directive emphasises on the definitions of bio-waste and recycling. It supports the inclusion of organic recycling (in the form of composting and anaerobic digestion of organic waste) in the definition of recycling and suggests a future-oriented definition of biowaste by taking into account other materials with similar biodegradability and compostability properties.

The EUBP says that these amendments are important to achieve higher recycling targets by making use of the enormous but yet untapped potential of organic waste and compostable products in Europe.

The largest fraction of municipal waste (up to 50%) in Europe is bio-waste, only 25% of which is currently collected and recycled.

The report calls for a mandatory collection of biowaste by 2020 supported by measures to increase the organic recycling of bio-waste to 65% by 2025. The proposed amendments also foresee limiting the amount of residual municipal waste landfilled to 25% by 2025 and to 5% by 2030.

Biodegradable plastic: an eco-friendly myth?

The sentiment against fossil-based plastics is spurring demand for greener plastics including biodegradable plastics, mostly used in packaging applications, in the hope that there will be an equally practical yet more ecologically-sound way to utilise plastics. However, a recent report from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has burst this bubble.

The Marine Plastic Debris and Microplastics report cites that biodegradable plastics are not necessarily better for oceans than traditional plastics.

Among the findings, biodegradable plastics do not break down in temperatures below 50°C, and they also contain additives that may contaminate the environment, not to mention render them difficult to recycle.

Furthermore, microplastics can be generated, thus contributing to marine litter. This is because, while biodegradable plastics are designed to degrade quickly in landfills, in nature, there is no such thing as ideal conditions for the products to degrade. Also, biodegradable plastics sink and therefore do not get exposed to UV rays to help them degrade. Plastics labelled as biodegradable do not degrade rapidly in the ocean, the UNEP report says.

There are some common polymers that are nonbiodegradable, such as PE. To enable more rapid fragmentation, PE is sometimes manufactured with a metal-based additive. However, UNEP says that there is no independent scientific evidence that biodegradation will occur any more rapidly than unmodified PE.

A prior report also stated that “the adoption of products labelled as biodegradable or oxo-degradable would not bring about a significant decrease either in the quantity of plastic entering the ocean or the risk of physical and chemical impacts on the marine environment, on the balance of current scientific evidence.”

As for biodegradable packaging, the New Plastics Economy espoused by EMF is unwrapping a “bio-benign” plastic packaging – one that would reduce its negative impact on natural systems when leaked, while also being recyclable and competitive in terms of functionality and costs.

EMF revealed that the current biodegradable plastics rarely measure up to that objective, as they are typically compostable only under controlled conditions.

Sustainability focus on packaging

Packaging can play a significant role in the New Plastics Economy, since it is the largest use in the industry, accounting for 26% of the total volume, the EMF report says. The volume growth for the sector is forecast to reach 318 million tonnes annually by 2050.

The flipside of this growth is that recovery remains low, with about 72% of plastic packaging not recovered and about 40% going into landfills, with the remaining 32% leaking out of the collection system. At least 8 million tonnes of plastics leak into oceans/year. If left unmitigated, the volume per minute of litter dumped into the oceans will double by 2030, and quadruple by 2050.

There are ways that the packaging industry is ruminating to contribute to the New Plastics Economy, through a low-carbon production process, with the utilisation of plants or organic resources, with less reliance on non-renewable resources.

A recent report from Smithers Pira shows that sustainability factor is becoming increasingly important across packaging value chains; and is at the crux of the economic, environmental and social objectives of the packaging industry.

Environmental consultancy Trucost in its study, Scaling sustainable plastics: Solutions to drive plastics towards a circular economy, finds that sustainable plastics use could potentially generate US$3.5 billion in environmental savings.

On the other hand, the environmental cost of using plastics is almost five times over or U$75 billion, due to climate change and pollution. It suggests that closed loop recycling, biobased and biodegradable plastics can bring on cost savings.

These findings are aimed to scale up the market for sustainable plastics but for the solutions to be picked up by the majority of plastic value chain is the focus of other studies.

A real solution in the long haul

Though the New Plastics Economy highlights the benefits of espousing a circular economy to create “long-term systemic value by fostering a working after-use economy”, it is not an instantaneous solution. It could take years to happen. The process requires redesigning materials, formats and systems, developing new technologies and evolving global value chains. “But this should not discourage stakeholders or lead to delays — on the contrary, the time to act is now,” the report advises.

Furthermore, UNEP suggests employing increased recycling collection, especially in countries that generate large volumes of waste plastic.

Meanwhile, efforts to curb waste plastic contamination are ongoing, but are not guaranteed to deliver 100% positive results. For example, biobased, compostable or biodegradable plastics tend to encourage littering among individuals that rely on the materials’ eco-friendly nature to biodegrade naturally.

The UNEP report says that there is limited evidence suggesting that some people are attracted by technological solutions as an alternative to changing behaviour. This is illustrated in labelling the product as biodegradable – a technical fix that takes away the responsibility from the individual to be more conscientious in disposing of waste plastics.

Needless to say, the essence of a successful plastics economy starts from an individual’s action to recover, recycle or reuse plastics that are consumed.

(PRA)Copyright (c) 2016 www.plasticsandrubberasia.com. All rights reserved.