Recycling medical devices through the thermochemical method

Medical waste being overlooked

Disposable healthcare items are creating enormous amounts of waste, which is incinerated, but in many countries ends up in landfills. The Covid pandemic was an eye-opener to the mountain of medical waste and contributed to an avalanche-like increase in disposable items being used. Worldwide, used face masks alone were estimated to weigh around 2,641 tonnes/day in 2022.

In circular economy policies, medical waste is often overlooked since disposable healthcare items usually consist of several types of plastic that cannot be recycled with today's technology.

In addition, the items must be considere d contaminated after use, and so, they must be handled so that risks of spreading potential infections are avoided. When it comes to the production of single-use healthcare items, it is also not possible to use recycled plastic, since the requirements for purity and quality are so high for materials intended for medical use.

Light at the end of tunnel for medical waste

Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, in Sweden, have now shown how mixed waste from healthcare can be recycled in a safe and efficient way, using a technique where the material is heated and converted into chemical building blocks, which can then be used in the production of new plastic.

The technology is called thermochemical recycling and is based on a process called steam cracking. It breaks down the waste by mixing it with sand at temperatures up to 800°C. The plastic molecules are then broken apart and converted into a gas, which contains building blocks for new plastic.

Martin Seemann, Associate Professor at Chalmers' Division of Energy Technology, says the method “destroys bacteria and other microorganisms”.

"What are left are different types of carbon and hydrocarbon compounds. These can then be separated and used in the petrochemical industry, to replace fossil materials that are currently used in production."

Great potential for saving valuable chemicals

To test the technology in real life, the researchers have carried out two different projects in parallel in a test facility at Chalmers Power Central.

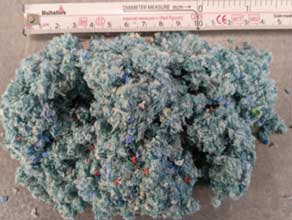

In the first project, a few different product types, such as face masks and plastic gloves, have gone through the process. In the second, a mixture was created that represents the average composition of hospital waste from the region's hospitals. The mixture contained about ten different plastic materials, as well as cellulose.

The results have been consistently positive in both projects, which shows the great potential that exists in the technology.

One of the projects was led by Judith González-Arias, now at the University of Seville in Spain, who says the method “facilitates the recovery of valuable carbon atoms”.

Furthermore, the researchers say this method is the “only” option available, given the strict regulations on medical use materials.

According to Seemann, "The same strict requirements for purity and quality actually also apply to food packaging. This is why the vast majority of plastic collected from packaging is incinerated today, or recycled into items where lower quality is allowed.”

The two projects build on previous Chalmers research, which has shown how mixed plastic waste can be converted into raw material for new plastic products of the highest possible quality.

The technology works well, but other factors also come into play

To scale up the method, new material flows and functioning business models need to be established, in collaboration between the healthcare and recycling sectors. Laws and regulations at different levels may also need to be changed in order for thermochemical recycling to be widely implemented in society.

Seemann adds, "For example, a requirement for carbon dioxide capture, when incinerating plastic, would create incentives to instead invest in more energy-efficient alternative technologies such as ours.”

Many countries have the technical prerequisites for recycling medical waste and other mixed plastic waste through steam cracking. However, regulations and structural conditions vary, which determines how players in waste management, the chemical industry and product manufacturing would need to work together to create functioning value chains in different places in the world.

Sweden lacks volume for thermochemical recycling

In Sweden, there is a great deal of interest in recycling, but single-use items from healthcare do not in themselves create large enough waste volumes for a functioning circular business model. Around 4,000 tonnes of such plastic were put on the market in the country in 2019.

"To build a plant of the size required for profitable thermochemical recycling, you would have to ensure a material flow of around 100,000 tonnes/year before startup," says González-Arias.

She says that new collaborations would therefore be needed between several different players for commercial thermochemical recycling, where healthcare waste could be part of the material flow.

The process would be optimised if a Swedish plant was built in an existing chemical cluster, such as the one in Stenungsund. The Chalmers researchers collaborated with Austrian polyolefins firm Borealis during the development of the technology since it has a steam cracker and related facilities there.

She says that new collaborations would therefore be needed between several different players for commercial thermochemical recycling, where healthcare waste could be part of the material flow.

The process would be optimised if a Swedish plant was built in an existing chemical cluster, such as the one in Stenungsund. The Chalmers researchers collaborated with Austrian polyolefins firm Borealis during the development of the technology since it has a steam cracker and related facilities there.

(PRA)SUBSCRIBE to Get the Latest Updates from PRA Click Here»