The ban on plastic bags and other plastic single-use products has reached fever pitch across the globe, in view of the collective response to environment protection. The antithesis is the shrinking demand and dwindling market, leading to loss of jobs. One country that has recently jumped on the ban-the-bag wagon is the Philippines, where it has become a political issue rather an environmental solution, and poses risks to the economy,

Early this year, 14 Philippine plastics industry groups, including the Philippine Plastics Industry Association (PPIA), the Association of Petrochemical Manufacturers of the Philippines, the Packaging Institute of the Philippines, the Polystyrene Packaging Council of the Philippines (PPCP) and the Metro Plastics Recycling Industries, placed advertisements in major newspapers to vilify what they said were unfair attacks against plastics.

Plastics were deemed to be the root cause of solid waste problems in the country, which therefore transpired an intensifying campaign to ban plastic bags, instituted by local government units (LGUs).

To date, over 60 cities and municipalities nationwide have imposed plastic bag bans or other regulations, from imposing recovery fees per use of bags to stiffer fines for businesses caught violating ordinance provisions.

While the ordinances have commonalties, there are variations in the proposed plastic bag alternatives and penalties. Short of an ultimatum, the plastics industry, which according to the Philippine Chemicals 2012-2030 Master Plan will be contributing significantly to the Php300 billion revenue projected in the chemicals, plastics and rubber sectors, is calling for a more informed campaign. Some suggestions include the implementation of systematic recovery, segregation and recycling schemes, based on the framework of the Philippine Republic Act (RA) 9003 (The Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000).

Why plastics?

Plastic bags and Styrofoam (PS foam) packaging were accused of being the main culprits for clogging up waterways and drains, thereby leading to extensive flooding in the country, during the Ondoy typhoon in 2009 and Habagat this year.

Peter Quintana, President of the Philippine Plastics Industry Association (PPIA), expresses his dismay over the growing anti-plastic sentiments. “Plastic products float and are thus visible, unlike other materials that submerge and tend to cause silting in flood waters,” he said during an interview at the recent Plastics Philippines show held 10-13 October at the SMX Convention Centre in Pasay City.

Echoing his statement was Daisy Concepcion Coroza, Secretary-General of the Polystyrene Packaging Council of the Philippines (PPCP), “Unfortunately, unlike other materials, plastic waste is easily seen and thus it is deemed an eyesore.”

Both agreed that misinformation about plastics and PS has led to this drastic campaign. It all started with the lead toxicity issue in plastic toys and plastic curtains. While agreeing that lead-based paint used in toys and the PVC component of shower curtains does pose risks, they say that “plastic, per se, is safe.”

“There are many types of plastics just like there are many types of paper,” Coroza said, adding, “The ban is based on non-scientific facts, like the fact that PS is not biodegradable. That is so passé since PS wastage can be recovered and recycled.”

Both plastics and paper are especially used in food packaging. “PS foam is increasingly being replaced with wax or plastic-lined paper. To recycle this type of paper, the wax or plastic lining has to be separated from the paper, which is a longer and more expensive process,” she explained.

She said that the association is encouraging its members to switch from PS foam to degradable food packaging, adding that bioplastics are also being eyed but compliance to food usage is still a stumbling block.

PPIA also debunks the notion that paper is an environment-friendly alternative in view of the fact that it takes 17 trees to make a tonne of paper and a gallon of water to make a single paper bag, using up to 300% more energy, whereas the same volume of water can produce 116 pieces of plastic bags.

This view is shared by Henry Gaw, President of PPCP, “Compared to plastic bags, paper bags are bulky and heavy (600% more) and more expensive (US$1.80 compared to US$0.60 cents for a plastic bag.” He also said that a PS foam cup only weighs 1 g whilst a paper cup weighs about 4 g.

Cardboard boxes, being alternative packaging in supermarkets and retail shops, are also posing problems to manufacturers of corrugated boxes. Gaw said that since these boxes are used for packaging, the stores no longer sell the boxes back to manufacturers, and thus the supply cycle is affected. Moreover when disposed improperly, just like paper, the heavier cardboard boxes sink to the bottom of waterways and cause silting; and since they are “unseen” also make waste collection a problem.

Over and above that consumers prefer plastic bags, Coroza added. “Since it is not a blanket ban, when plastic bags are used, supermarkets report higher sales, compared to when paper bags are used.” She also said that more staff is required to do the packing in paper bags.

Alternative to plastic bags

Meanwhile, Pasig City, one of the local government units in Manila (dubbed as the recycling capital of the Philippines) that has implemented the plastic bag ban under the City Ordinance, is offering an alternative.

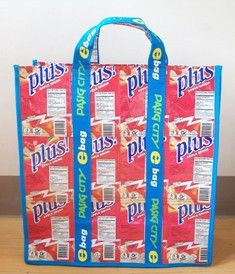

Led by the City Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO), a project team is recycling waste from aluminium doy packaging (used for juices and drinks) by sewing it into bags with fabric straps.

Speaking to PRA at Pasig City Hall, Raquel Naciongayo, Head of CENRO, said that the Eco-bag is a durable alternative. “It is indestructible for 50 years!,” she said, adding that the Eco-bag is also targeted at export markets, retailing at Php2,000 (US$40) a piece. Domestically, it is retailed at Php200 (about US$4) outside the city and 50% less in the city since the cost is partly subsidised by the local government.

Other alternatives include bags made of tarpaulin scraps and nonwoven fabric. The bags are produced by local community groups, as part of the city’s livelihood programme, involving 6,000 families in the city, thus creating jobs and improving living standards.

The CENRO chief also explained that whilst the authorities are open to reviewing the ordinance, the probability of changing the provision depends on whether the National Government with the Department of Natural Environment and Resources (DENR) will issue an official statement in favour of plastics and PS foam. At the moment, Naciongayo said that the ordinance’s provisions will remain.

Not helping the economy

However, not all groups are in favour of the shift to paper and non-woven bags. “It is not helping the local economy,” said Quintana, explaining that the materials are imported. “We are giving jobs and opportunities to China and other countries,” he said, adding that in 2011 alone, the country imported 14,000 tonnes of paper, an increase of 45% over the previous year.

The plastics industry employs 175,000 direct and indirect workers. With the plastic bag ban, 30% of the workforce has lost jobs and work days have been reduced to four days, whilst some jobs have become seasonal.

In fact, Quintana says the outlook for the industry is bleak, adding that the ban is counter-productive and will ultimately affect the overall economy.

Drawing the worst scenario for the country if the outright ban continues, he said that the manufacturing industry will suffer; discouraging further investments and reducing the country to a trading hub.

Based on a recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) country report, manufacturing comprised 33.3% of the country’s GDP, with chemical products, including plastics, as strong industry drivers.

Crispian Lao, former President of the PPIA, says a factor in favour of the plastics industry is that it is an equal opportunity industry that employs workers regardless of their academic status and working age. “The second generation manufacturers have workers that are above 60 years as well as youths just out of school,” he explained, adding that this is an incentive to keep the workforce employed.

A needed respite

Amidst all of this, a ray of hope shines bright as locals hinge on potential foreign investments to bail out the industry. For instance, recent talks were held with Japanese investors under the auspices of the Philippine-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (Pjepa).

Likewise, several industry groups are also embarking on recovery schemes to recycle waste plastics into consumer products.

But above all, the best solution is to go back to the basics. Lao says that about 45% of plastic waste is not disposed or segregated properly and calls for a concerted effort in this area. “The plastic ban has become politically popular but is it the right way to go?” he asks, adding that the authorities need to look at countries like Japan that has an extensive recycling programme in place.

The industry is also pushing for the full implementation of the Comprehensive Solid Waste Management System of the RA 9003, which already has the necessary effective measures to reduce waste problem, including mandating the LGUs to establish respective waste management and segregation systems.

Quintana adds, “We were not well represented when cities started implementing the plastic ban drive. We are now taking every opportunity to intensify our campaign and inform people about plastics.”

But above that Quintana said that consumers need to be educated on waste disposal habits while Gaw stressed that discipline needs to be instituted. “If we continue to litter indiscriminately, whether it is paper or plastics, the waste will end up clogging drains and waterways.”

In conclusion, both agreed that disciplined segregation of waste and recycling is what is required. “That is the real solution,” opined both industry leaders.

(PRA)