Materials News: Having your fill of “edible” plastics

Also, download this story from the electronic issue here

Bioplastics development is becoming more “appetising” with the innovation of food-based packaging materials, says Angelica Buan in this report. These are said to be safe when eaten by animals and marine life, and some are even safe for human consumption! Materials

Plastics “food” in the sea

The smorgasbord of plastics waste in the ocean may be an eyesore for humans but for marine animals the plastics stew is a gastronomic lure!

A 2016 study published in Science Advances found that algae, which can thrive on waste plastics in the oceans, emit an odour of a gas known as dimethylsulphide (DMS). Marine animals (and even sea birds), with a keen olfactory sense, follow the scent that normally leads to a banquet of small crustaceans – their natural prey.

However, with the oceans inundated with waste plastics, marine animals that follow the DMS trail are instead being led to a lethal buffet of plastics, instead of their natural prey! An estimated two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks ingest plastics, according to Australia-based Ocean Crusaders Foundation, feeding on largesse of some 46,000 pieces of plastics per square mile of ocean.

Clean-up efforts have been started by some groups, notably the Netherlands-based The Ocean Cleanup, which is gearing for its large-scale clean-up of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch by 2020. Later this year, the team will be launching and deploying the world’s first operational ocean clean-up system called Pilot. It utilises the natural ocean currents to catch marine debris, hence doing away with any external energy source, the organisation states.

Nevertheless, even with such model technology in place, it may take decades to clean the oceans of waste plastics, or at least to that level when plastics consumption was not as wide-scale as it is now.

Curbing waste through bioplastics

Waste management, particularly recycling, is a common and practical approach to curbing land-based plastic waste, a fair amount of which enters the waterways. However, technical, institutional, financial and social constraints, particularly in developing countries, hound waste management efforts.

On the part of plastic producers and users, a doable solution is replacing conventional plastics that do not biodegrade on land or in water (unless additives are added to materials during production) with plant-based plastics/ bioplastics.

The market for bioplastics is projected to grow at a CAGR of 28.8% or close to US$44 billion by 2020, a report from Future Market Insights (FMI) says. It will be mainly driven by a growing packaging industry.

But even with the “promise” of being biodegradable, some experts are sceptical if bioplastics can solve the marine debris problem.

An article published by US-based marine environment research organisation Algalita questions if bioplastics are able to degrade better in the environment than oil-based plastics, in reference to the two test standards that gauge biodegradation of plastics: ASTM and ISO. The latter tests distinguish key terms such as degradable, biodegradable and compostable.

Meanwhile, New York-headquartered Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI) also released a white paper on biodegradability. It says that not all biobased materials are necessarily biodegradable, for example some forms of cellulose. It also suggests that the only way to know if the material or product is biodegradable or compostable is if it meets the ASTMD6400 (for compostable plastics) or D6868 (for compostable packaging). The test determines the percentage of the product that comes from renewable resources.

Nonetheless, as developments for novel biobased materials continue to unfold, existing standards for biodegradability and compostability may have to be reworked, say experts.

Biodegradable bag solutions on the table

A new generation of compostable plastics and plastic substitutes made from food feedstock are claimed to be safe, so safe that they can be eaten. Even so, the so-called “edible” plastics, as palatable as it may sound, are not meant to be a main fare in anyone’s lunchboxes, but more for marine species in the ocean and insects in the soil.

Made from all food-based feedstock, this generation of bioplastics are purported to be non-toxic, thus, safe for the environment.

Indonesian chemicals company Inter Aneka Lestari Kimia launched in 2011 its starch-based Enviplast pellets and bags/ film. The company points out that the Enviplast bags are not similar to plastic bags, “even though the manufacturing process and appearance are similar to conventional plastic bags.”

"Enviplast bags are not plastic bags because they contain no PE at all," according to Sri Megawati, Sales & Marketing Executive for Enviplast. As proof, Megawati suggests several tests. "You may dissolve it in hot water or burn it and it will not leave any melted residue or release toxic fumes. Even if you place a hot iron on the surface, it will not melt, but will be scorched like paper," she said. Enviplast bags are also safe for the environment; and can be consumed by snails, insects, and other land and aquatic animals, she adds.

The company also says that Enviplast’s oxygen barrier makes it suitable for use as a secondary or a multi-layer packaging. Additionally, the Enviplast composite pellets cost lower, compared to other compostable plastic pellets available in the market, a factor that is seen to be a downside for the mass use of bioplastics, compared to conventional plastics.

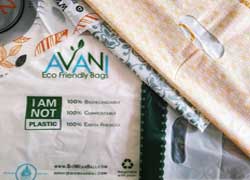

Another company promoting starch-based biopolymers is Avani. The Indonesia-based social enterprise says that its Avani ecobags are 100% compostable, biodegrade in a short period of three to six months, depending on soil conditions; and break down to carbon dioxide and water without leaving behind any toxic residue. Made from cassava and other natural resins, Avani ecobags dissolve completely over time and have also passed the Oral Toxicity Test certification, indicating that the bags are safe for marine species when ingested.

Meanwhile, Envigreen Biotech India has launched a 100%

biodegradable bag made from tapioca, potato, and vegetable

oil derivatives and wastes. Claiming to be non-toxic and

safe for the environment, animals, and plants, the patented

Envigreen material can be dissolved in hot water (80°C)

and softens in water at room temperature. When disposed,

the company says its bags take less than six months to

biodegrade, and thus are harmless to the environment or if

eaten by animals.

safe for the environment, animals, and plants, the patented

Envigreen material can be dissolved in hot water (80°C)

and softens in water at room temperature. When disposed,

the company says its bags take less than six months to

biodegrade, and thus are harmless to the environment or if

eaten by animals.

However, in terms of cost, the EnviGreen bag is 35% more expensive than the cost of a regular plastic bag but significantly cheaper than cloth bags, according to Ashwath Hegde, the company’s founder.

Plastic film created from milk protein

Milk protein is the key ingredient of an edible plastic being developed by a team of scientists, according to the American Chemical Society (ACS).

The packaging film is not only edible it also features better barrier performance, said to be up to 500 times more effective in barring oxygen from food, thus, helping prevent food spoilage, compared to thin films.

The film is made of casein, a milk protein, making it

edible, biodegradable and sustainable. Some commercially

available edible packaging varieties are already on the

market, but these are made of starch, which is more porous

and allows oxygen to seep through its microholes. The milkbased

packaging, however, has smaller pores and can thus

create a tighter network that keeps oxygen out.

available edible packaging varieties are already on the

market, but these are made of starch, which is more porous

and allows oxygen to seep through its microholes. The milkbased

packaging, however, has smaller pores and can thus

create a tighter network that keeps oxygen out.

Although the researchers’ first attempt using pure casein resulted in a strong and effective oxygen blocker, it was relatively hard to handle and would dissolve in water too quickly. They made some improvements by incorporating citrus pectin into the blend to make the packaging even stronger, as well as more resistant to humidity and high temperatures.

After a few additional improvements, this casein-based packaging looks similar to plastic wrap, but is less stretchy and better at blocking oxygen. Nutritious additives such as vitamins, probiotics and nutraceuticals could be included in the future. It does not have much taste, the researchers say, but flavorings could be added.

The researchers are exploring its potential as a singleserve, edible food wrapper. Because single-serve pouches would need to stay sanitary, they would have to be encased in a larger plastic or cardboard container for sale on store shelves to prevent them from getting wet or dirty.

The casein could also be used as a spray onto food to keep the crunchiness and coat containers since the US Food & Drug Administration recently banned perfluorinated substances that are used to coat containers.

Funded by the US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service, the scientists plan to keep making improvements, with casein packaging expected to be launched within three years.

Discarded food powers in barrier solutions

US company Apeel Sciences utilises agricultural by-products

that are typically discarded (like grape skins from wine

production, for example, or broccoli stems) and engineers

them into a micro-thin, invisible, tasteless “barrier” that can

be applied to fruits and vegetables. The company hopes

to dramatically extend the shelf life, thus, cutting down on

the amount of produce wasted and also allow growers to

harvest produce at its peak ripeness. Application can be done in a variety of ways, Apeel said,

including widely-used spray, dip and paint-on methods.

them into a micro-thin, invisible, tasteless “barrier” that can

be applied to fruits and vegetables. The company hopes

to dramatically extend the shelf life, thus, cutting down on

the amount of produce wasted and also allow growers to

harvest produce at its peak ripeness. Application can be done in a variety of ways, Apeel said,

including widely-used spray, dip and paint-on methods.

Currently in the R&D phase are Invisipeel, created to protect crops at pre-harvest stage, and Edipeel, a postharvest barrier solution. This year, the company is fielding Edipeel for use by selected growers and producers, following testing success in field trials and on commercial applications in 2016.

Another innovation that repurposes food waste has

been developed by researchers at Brazil’s Embrapa

Instrumentation under the Nanotechnology Applied to

Agribusiness Network (AgroNano) project. The edible films

can be made from spinach, papaya, guava, tomato and other

fruits and vegetables; these are then dehydrated and mixed

with a nanomaterial to bind it.

fruits and vegetables; these are then dehydrated and mixed

with a nanomaterial to bind it.

Chief researcher, Luiz Henrique Capparelli Mattoso, explained that food industry waste can be used to process the material, which then ensures two sustainability characteristics, namely, the use of food waste and the substitution of a synthetic packaging that would be discarded.

He explains that the material is not only safe when ingested, but also endows physical characteristics akin to conventional plastic, such as resistance and texture as well as equal capacity of protecting food.

Another tropical fruit, worth mentioning, has been developed into edible biomaterial. In a six-month study carried out in 2014, researchers at the Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Bogor Agricultural University, Indonesia, made edible film and packaging using banana skin as a raw material. A horticultural crop, banana is abundant in Indonesia. Its skin, as a by-product of industrial processing, is no longer economically viable, yet as a raw material can be environmentally-friendly.

According to the research team, banana skin contains the pectin compound, which has good gel properties suitable for producing edible packaging. The pectin is extracted from the peel. For the plastic to acquire elasticity, glycerol is added.

As such, researchers all over the world are working on creating all-around better packaging solutions that are environmentally friendly as well.

(PRA)Copyright (c) 2017 www.plasticsandrubberasia.com. All rights reserved.